How Musical Stresses Work: Rhythmic Metric and Melodic Stress

Rhythmic stress is the perceived importance of an attackA term describing the point in time when a note first begins. This is the moment the piano key is pushed or the guitar string is plucked. based on its position within a rhythmic structure.

In any set, some members will have a special position. For instance, the first and the last members usually play a key role. In rhythm, we have a repeated set of units called the pulseUsually used to indicate the repetition of a single rhythmic value. This pulse can then be used to create sub-divisions and other rhythms.. Often the pulse is clearly stated by a percussion instrument such as drumset.

Pulse

Definition of the pulse

The pulse will not always be clearly stated in the music, but it will be the guide for all rhythm. Consider the architect’s graph paper. Although a grid of small squares is used to guide the drawing, those squares are not needed in the result.

Speed of the pulse

The speed of the pulse is described in terms of BPM(Beats Per Minute) — The number of pulses in the duration of 60 seconds. A clock ticks at a rate of 60 beats per minute. or beats-per-minute. Of course, a ticking clock will have 60 beats per minute, if it works correctly.

Rules of Pulse

By nature, the pulse is:

- Repeated, from the beginning of the musical section or song to its end.

- Divided into groups of 2, 3 or 4, or some combination of these.

- All pulses are completely even with respect to each other. That is, each pulse is exactly the same length. This is especially true of dance and electric music, and most modern music. However, in music played by humans without machine assistance the pulse will naturally vary to a slight degree. And in some music, such as classical music, the pulse will ebb and flow.

Pulse Groupings

Rhythmic stress refers to the perceived importance of a rhythm given its relation to the pulse. Here is an overview of some of the more common pulse groupings, and how they impact rhythmic stress.

In the following examples, the relative strength or weakness of a beat will be expressed by how high that note is on the staff. These notes do not represent pitches, but rather the strength of a given beat based on its position.

Basic Pulse Groups

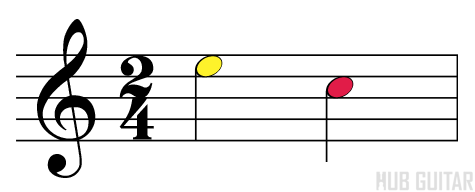

Cut Time

In cut time (two quarter notes per measure), the stress pattern is simply “strong, weak”.

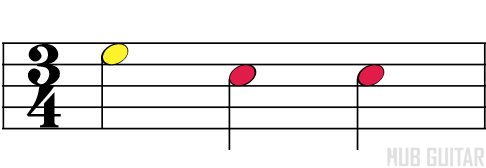

Waltz Time

In waltz time, the stress pattern is “STRONG, weak, weak”.

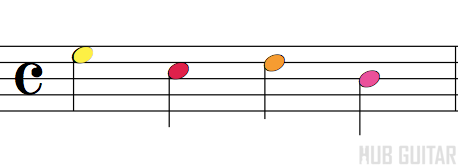

Common Time

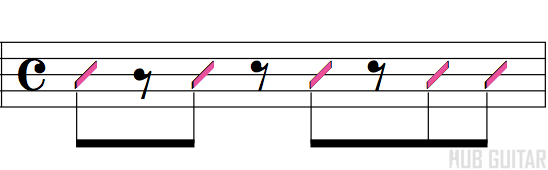

In common time, the stress pattern is “STRONG, WEAK, strong, weak”. It doesn’t matter what the actual rhythm is. The underlying stress pattern is indicated on top. Any rhythms played in this meter will be heard with that stress pattern.

In the below example, the first attack would be heard as relatively strong. The second beat has a rest, followed by an eighth note attack on the “and of 2”; this beat is even weaker than 2, and tends to be heard as a part of the second beat.

In other words, notes in sub-divided beats tend to inherit the stress of the beat they're a part of.

Regardless of the actual rhythm played, the stress pattern of the meter plays a part in how that rhythm is heard.

Asymmetrical Pulse Groups

Asymmetrical compound pulse groups are time signatures that result in 5, 7 or 11 pulses. Others are possible but increasingly less likely as higher numbers can be considered multiples of the lower numbers.

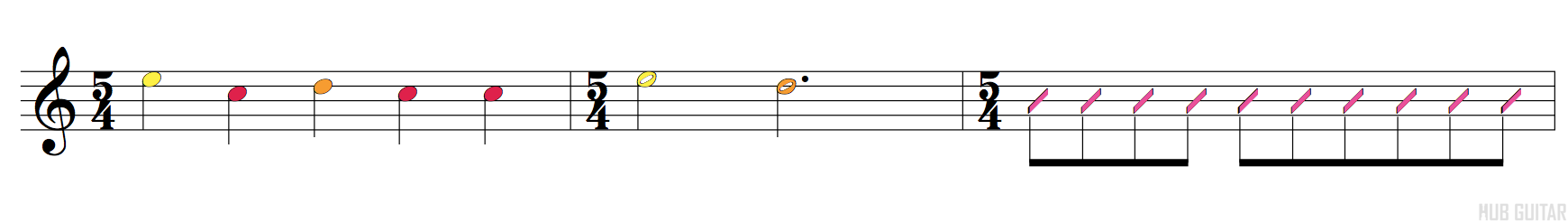

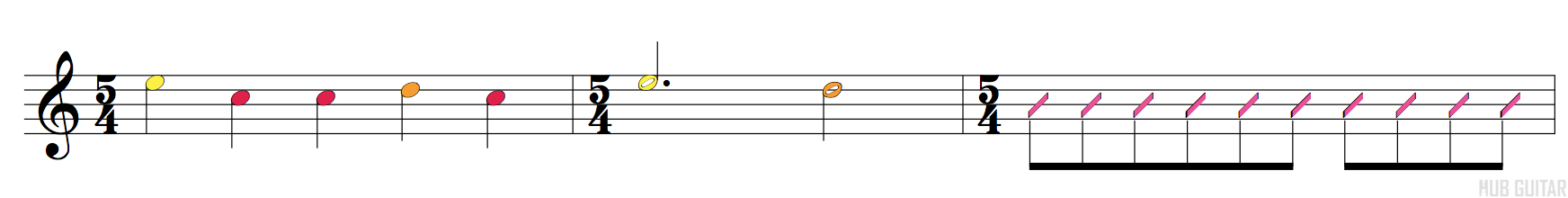

5 Pulses (2+3)

The 2+3 pulse pattern can be viewed as a combination of one measure of cut time, and one measure of waltz-time. The strongest beats are 1 and 3, which are then sub-divided into other patterns.

It is important to show this distinction, especially in eighth note groupings (right). Notice how the beams connecting the eighth notes stop before beat 3, showing a clear distinction between the beats.

5 Pulses (3+2)

The 3+2 pulse pattern can be viewed as a combination of one measure of waltz-time, and one measure of cut time. The strongest beats are 1 and 4.

As above, note how beats 1 and 4 are shown clearly in the written music.

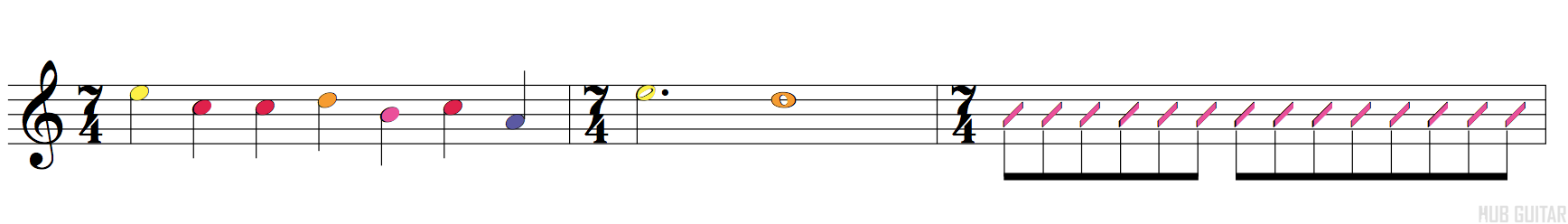

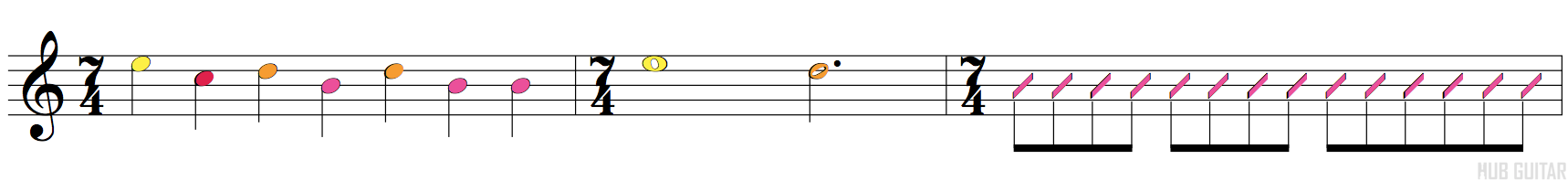

7 Pulses (3+4)

The 3+4 pulse pattern can be seen as a combination of one measure of waltz-time, and one measure of common time. The strongest beats are 1 and 4.

Note how beats 1 and 4 are shown clearly.

7 Pulses (4+3)

The 4+3 pulse pattern can be seen as a combination of one measure of common time, and one measure of waltz-time. The strongest beats are 1 and 5.

Note how beats 1 and 5 are shown clearly.

Compound Pulse Groups

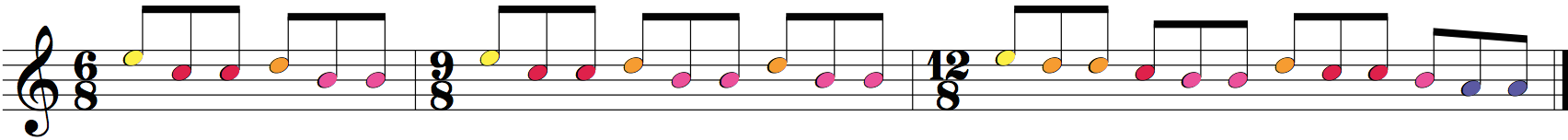

Compound pulse groups are normally of the simple variety (2, 3 or 4 pulses) but each of these pulses are also divided again, usually by 3.

Using the above example, we can have two pulses of three (6/8), three pulses of three (9/8) or 4 pulses of three (12/8). It’s also possible, if uncommon, to combine compound and asymmetrical pulses, for instance with five pulses of three (15/8).

Whatever the pulse grouping is, the music should be clearly written to mark and clarify the pulse.

How Stress Affects Melodies

The relationship between metric stress and the melody is nuanced. Generally, notes of the melody will inherit a stress from the beat that they begin on or begin near. For instance, a melody note beginning just a sixteenth note after beat 1 will tend to have a strong stress. It will tend to be heard more as an attack on beat 1 that was delayed.

As the creator of Hub Guitar, Grey has compiled hundreds of guitar lessons, written several books, and filmed hundreds of video lessons. He teaches private lessons in his Boston studio, as well as via video chat through TakeLessons.

As the creator of Hub Guitar, Grey has compiled hundreds of guitar lessons, written several books, and filmed hundreds of video lessons. He teaches private lessons in his Boston studio, as well as via video chat through TakeLessons.